When discussing Edinburgh’s architectural grandeur, the mind immediately conjures images of stone facades, symmetrical colonnades, and the stark harmony of its lines. It is no coincidence that the city earned the title “Athens of the North,” as it was here in the 19th century that the unparalleled talent of William Henry Playfair flourished. His works, beyond their aesthetic ideals, embodied the ambitions of an entire generation—a desire to merge the beauty of the ancient past with the dynamism of the modern world. Read more on iedinburgh.

This article aims to explore the life and creative legacy of one of Britain’s most influential neoclassical architects. We will trace the path of his life, from his family beginnings to the creation of the iconic buildings that have defined the appearance of modern Edinburgh.

An Enlightenment Upbringing

William Henry Playfair was born on 15 July 1790 (though some sources suggest 1789) in London. From the very beginning, his family was immersed in the art of building: his father, James Playfair, was an architect. Following his father’s premature death, his mother was forced to move with her son to Edinburgh, where they were taken under the care of her late husband’s brother, Professor John Playfair. He was an extraordinary figure: a distinguished mathematician, geologist, and a highly influential member of the Scottish Enlightenment. Being in his household provided the young William with constant encouragement for deep, scientifically grounded thinking. His uncle took responsibility for his nephew’s education, laying a strong foundation of knowledge that would later, in a remarkable way, be reflected in the logical purity of his architectural forms.

The Dawn of a Career

Completing his theoretical training made Playfair realise the necessity of acquiring practical skills. He became an assistant to the well-known architect of the time, William Stark, who held a respectable position in Glasgow. Unfortunately, their collaboration was short-lived. Stark’s unexpected death in 1813 meant the young man had to forge his own path. He spent some time in London before embarking on a journey through France three years later. This whirlwind of travel allowed him to enrich his intellectual knowledge through direct observation of the classical architecture popular across Europe.

William received his first major project in 1815 when he was involved in the ambitious planning for a part of the New Town. Later, fate presented him with the opportunity to win a competition to complete the Old College, a project started by the legendary Robert Adam. The successful completion of such a landmark work brought him considerable recognition among local clients.

His life came to an end on 19 March 1857. He was buried in Dean Cemetery, where he had previously designed several tombs.

Playfair’s Signature Style

The architect’s style is defined as Greek Revival. His aesthetic creed was based on a strict logic rooted in the principles of antiquity. He favoured clean lines, rigid symmetries, and flawless proportions, while also employing canonical elements such as powerful columns, pilasters, elegant pediments, and porticos.

However, a defining feature of his work will forever remain his masterful play of light and shadow. Through window niches, cornice modulations, and alternating facade recesses, the architect achieved a living, plastic effect. Edinburgh’s unique northern light perfectly accentuated this monumentality, making the buildings seem to strive for dynamism.

An Urban Vision

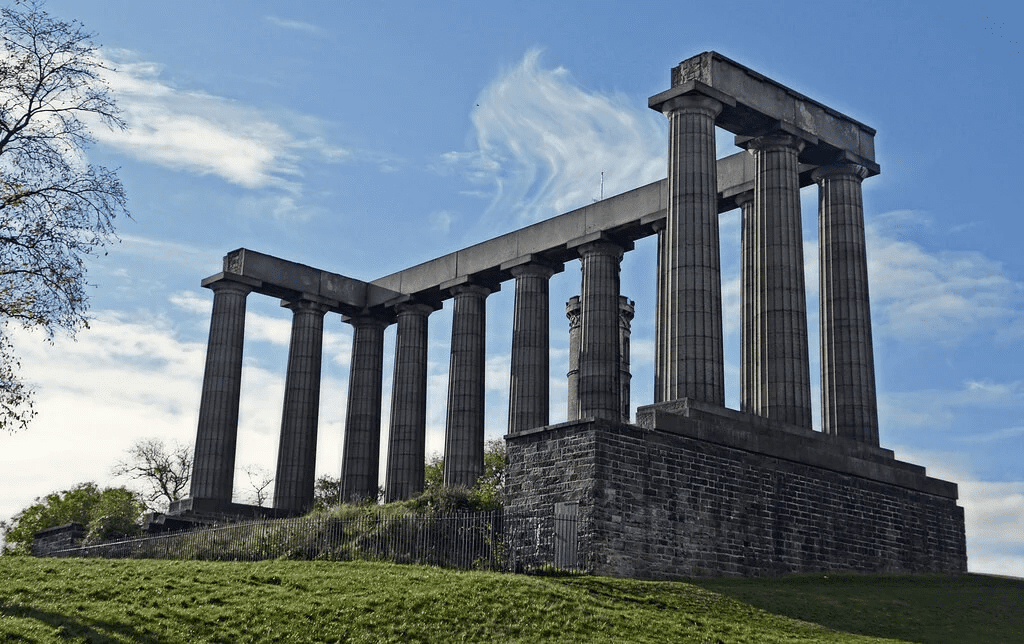

His true genius, however, can be seen in his work on Calton Hill. William created a series of magnificent terraces—Regent Terrace, Royal Terrace, and Carlton Terrace. He positioned them to take full advantage of the Scottish capital’s terrain and to provide panoramic views over the Firth of Forth. In one of his innovative practices, he would leave one side of the street undeveloped, while the opposite side served as an open space or green area.

Furthermore, a deliberate “connectedness” can be observed in his structures. For example, the locations of the National Gallery of Scotland and the Royal Scottish Academy were thoughtfully planned so that their facades would harmoniously “communicate” with each other in the space, forming a single artistic complex.

Anatomy of Key Projects

Although we have already mentioned his most significant buildings, a true understanding of this British genius requires a more detailed look:

- Old College. Here, Playfair sought to stylistically modernise the interior. He preserved the overall symmetry of the facade, but the corridors, stairs, and interiors were completely redesigned according to his plans. An ideal balance between substance and “air” is maintained in the halls.

- Dugald Stewart Monument. The architect drew inspiration from another masterpiece—the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates in Athens—to create a refined architectural form for the Scottish skyline.

- National Monument. The project called for an exact reproduction of the Parthenon as a war memorial—an act of extreme stylistic precision. The fact that it was left unfinished due to a lack of funding only enhanced its symbolic meaning: it became a symbol of Edinburgh’s unattainable dream of absolute grandeur.