Throughout the history of philosophy, few have had the courage to question reason itself. David Hume was one of them. He shunned the glory of a prophet, seeking neither followers nor disciples—only truth. It was a truth so stark that even doubt itself took shape. His thinking was born from a sense of the fragility of human knowledge: we perceive only a fraction of reality. The rest, he argued, is a product of habit, belief, and emotion. Read more on iedinburgh.

This article aims to explore the incredible journey of this profound thinker. His biography is a key to understanding an entire intellectual revolution. We will delve into the Scottish Enlightenment—an era where science fought for the right to define the concept of self—and examine its role in cultivating a generation capable of independent thought.

The Making of a Genius

David Hume’s life began in the somewhat austere climate of Edinburgh on 7 May (26 April, Old Style) 1711. He belonged to the Scottish gentry, a respected though not exceptionally wealthy class. His family name was originally Home, but the young David changed the spelling to Hume, likely because the English found the original pronunciation difficult.

The family estate, Ninewells, in the border county of Berwickshire, served as the family home, offering a balance between the intellectual environment of the city and the rural tranquility necessary for contemplation. However, the future philosopher’s childhood was overshadowed by an early loss: his father, a lawyer, passed away. The responsibility of raising the three children—David, his brother, and his sister—fell to his mother, Katherine Falconer Home. She quickly recognised in her son what she later described as an “uncommonly wake-minded” nature—a remarkably perceptive intellect.

At the tender age of twelve, when his peers were just beginning to delve deeper into Latin, Hume enrolled at the University of Edinburgh. There, he immersed himself in the study of literature, history, ancient and modern philosophy, and the fundamentals of mathematics and the natural sciences.

A Treatise of Human Nature

Seeking an escape from his routine, Hume travelled to France. Around 1734, he settled in the relative tranquility of La Flèche. The location held a certain symbolic significance, as it was where René Descartes, whose rationalist doctrines Hume sought to refute, had once been educated. The French environment inspired the young Scot to study the works of continental thinkers such as Nicolas Malebranche, Pierre Bayle, and Jean-Baptiste Dubos.

Over four intense years, Hume, then barely twenty-five years old, completed his monumental work, “A Treatise of Human Nature.” Its central idea was to apply the experimental method to moral subjects, following Isaac Newton’s example in physics.

Here are the cornerstones of his scepticism:

- The distinction between impressions and ideas. He argued that our entire mental world reduces to experiences—direct sensory data, or ‘impressions’, and ‘ideas’, which are merely faint copies of these impressions.

- The critique of causality. The philosopher argued that we have no genuine impression of the necessary connection between cause and effect. We merely observe a sequence of events. Our belief in causality, therefore, is simply a result of custom or the habitual expectation of our minds.

- Natural beliefs. As humans, we are compelled to believe in causality, the existence of the external world, and a consistent ‘self’. However, this compulsion is psychological. These intuitive beliefs, while essential for life, cannot withstand the test of rigorous logic.

The “Treatise” was published in parts: the first two books, “Of the Understanding” and “Of the Passions”, appeared in 1739, followed by the third, “Of Morals”, in 1740.

To his great dismay, the academic community met the work with striking indifference. This failure was a painful blow to his youthful ambitions, but today, the work is rightly recognised as one of the most important in the history of philosophy.

Trial by Fire

His first major disappointment was his attempt to secure an academic position. In 1745, he applied for the Chair of Ethics and Pneumatical Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh. However, his reputation for scepticism—and suspicions that he was undermining Christian dogma—provoked powerful opposition from the conservative clergy. Hume’s candidacy was rejected. A similar fate awaited the Edinburgh native’s applications to other universities.

Unable to establish himself within the walls of academia, Hume turned to other fields. He served as secretary to General James St Clair, a role that required considerable diplomatic skill. His new duties gave him the opportunity to travel across the continent, where he gained first-hand experience of its social and political life.

A Long-Awaited Triumph

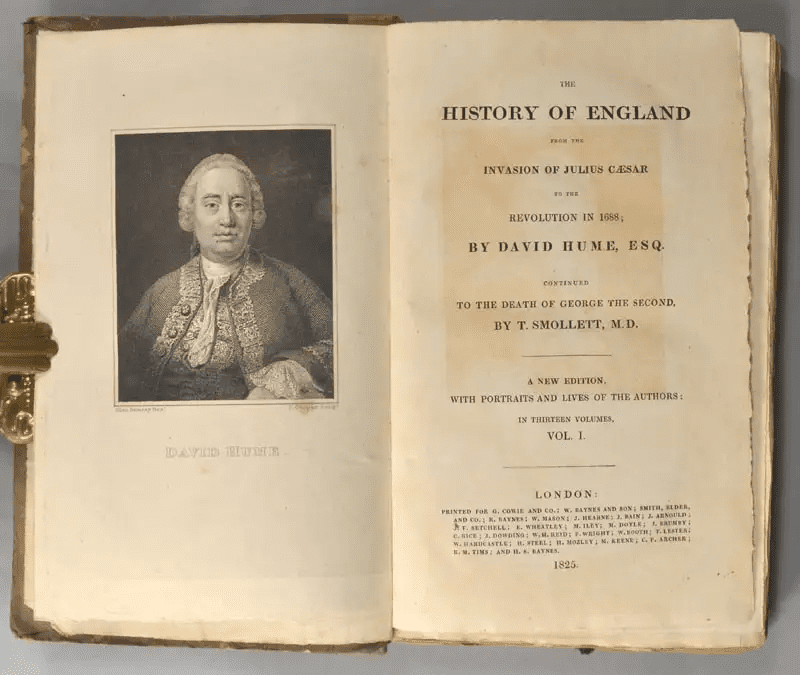

It was during his travels that Hume began working on “The History of England.” Unlike the aforementioned “Treatise,” this monumental work, published in volumes, was an immediate success. Its success was due to his approach of examining historical data as an analysis of social institutions. Although his Tory sympathies and critical perspective on certain events sparked controversy, the book became an enduring bestseller.

Hume died on 25 August 1776 in Edinburgh. His tomb, simple yet grand, rests in the quiet of the Old Calton Burial Ground.